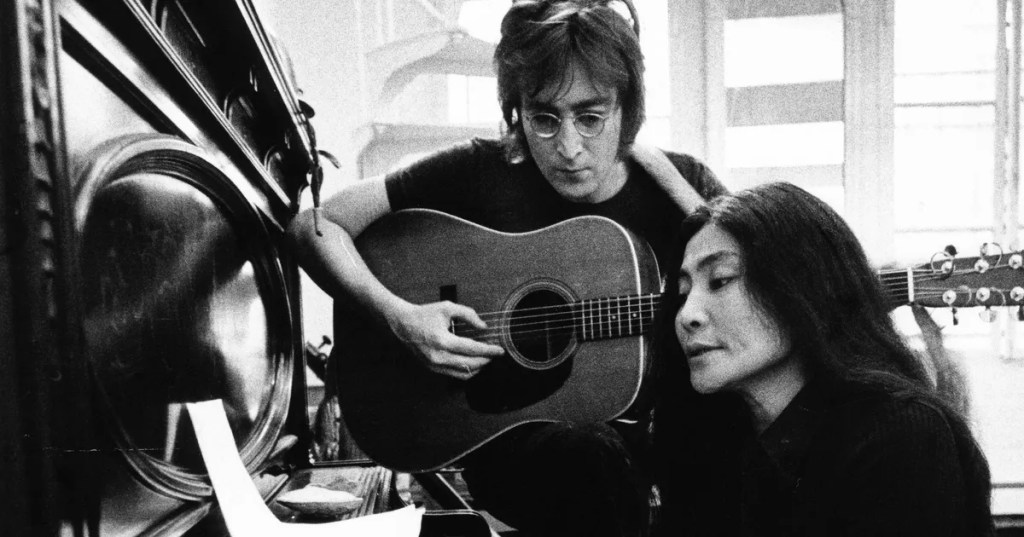

‘One to One: John & Yoko’ (2024)

The latest from Kevin Macdonald (“Touching the Void,” “Last King of Scotland”), working with Sam Rice-Edwards, delves into the life and times of John Lennon and Yoko Ono in New York City during the tumultuous Richard Nixon and Vietnam War era. It’s a spry, electric rewind with sharp, well-cut footage of the time and, naturally, the music and idealistic political activism of Lennon and Ono. Leaving their massive estate in London post-Beatles breakup, Lennon and Ono came to America to try to find Kyoko Chan Cox, Ono’s daughter from an earlier marriage to jazz musician Anthony Cox, who defied a court order and hid her from Ono. Lennon and Ono, in alignment with their ideology, opted to live “plainly” in the middle of New York – a decision that would factor into Lennon’s very public murder in 1980. The focus of the film is the “One to One” concert Lennon and Ono put on at Madison Square Garden in 1972 to benefit the children of the Willowbrook State School on Staten Island, shut down in 1987 but at the time the largest institution in the country caring for children with Trisomy 21 and other developmental disabilities. The concert was a reaction to an exposé by Geraldo Rivera of the inhumane, overcrowded conditions – there was one caregiver for every 30 children (the concert’s title offers a better ratio), living in squalor on cold cement. What’s shown is horrific (think Frederick Wiseman’s “Titicut Follies”). Filling out the frame of this conflict-rich time capsule are the shenanigans of Nixon, the bravery of Shirley Chisholm and the kindness she extended to a wounded George Wallace, a jazzed-up Jerry Rubin, poet and defiant pacifist Allen Ginsberg and Bob Dylan and his controversial “garbologist,” A.J. Weberman. It’s a wild olio that captures the chaotic time with Lennon and Ono at the fore, on point and putting themselves out there in every sense of the word. You have to admire their cool, calm and rapier-sharp responses, especially Ono, fighting to see her daughter and often tagged “an ugly J*#!, who broke up the Beatles.” There’s a bit about Cambridge too, with Ono as a speaker at the First International Feminist Conference held at Harvard University. If you’re not left verklempt by the end sequence, of kids from Willowbrook in daylight, beaming, cross-cut with Lennon and Ono performing classics such as “Imagine” and “Come Together” with Stevie Wonder and Roberta Flack, you need to get to the doctor to see if you have a heartbeat.

‘Nouvelle Vague’ (2025)

Richard Linklater’s love letter to the French New Wave is driven by the unwavering, near-maniacal vision of first-time filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard (Guillaume Marbeck) shooting “Breathless” in the Paris of 1959 (the film was released in 1960) with his stars: a relatively unknown Jean-Paul Belmondo (Aubry Dullin) and reluctant American actor Jean Seberg (Zoey Deutch, “Juror #2”) seeking a breakthrough after minor successes in Otto Preminger’s “Saint Joan” (1957) and “Bonjour Tristesse” (1958). The film homes in on Godard’s angst as the last of the young French auteurs to try to make his mark on French cinema – fellow cultural critics at the magazine Cahiers du Cinéma François Truffaut (Adrien Rouyard) and Eric Rohmer (Côme Thieulin) were already moving away from their typewriters and into the directorial chair and had first films in the can (“The 400 Blows” for Truffaut). The spry script by Vincent Palmo Jr. and Holly Gent, who partnered with Linklater on “Me and Orson Welles” (2008), make the impetus for Godard’s signature undertaking as something like Fomo. The film walks through the 20 or so days it took to shoot the très French gangster noir guerrilla style, with improvisational camera innovations that changed how films would be made. The biggest hurdle was Godard’s cryptic, quirky personality, which often alienated the cast (Seberg wanted to quit) and pissed off producer Georges de Beauregard (Bruno Dreyfürst) so much so that the two come to blows. The meticulous recreation of the time and place is mind-boggling, and the number of personalities brought to life rivals “Midnight in Paris.” Linklater even frames “Nouvelle Vague” in polished black-and-white, with a 4:3 aspect ratio to invoke the look of the era. Most of the action hangs on Godard and Seberg (Belmondo is more of a sidecar), and Marbeck and Deutch give rich performances that feel deeply researched and genuinely lived in. Among the many notable cinematic faces in small bits are Claude Chabrol (who, along with Truffaut, helped conceive the storyline for “Breathless”), Jacques Rivette, Agnès Varda, Jacques Demy, Jean-Pierre Melville, Roberto Rossellini and Robert Bresson. Linklater’s tender, and maybe too adoring, time capsule pairs well with “Blue Moon,” his biographical embrace of songwriter Lorenz Hart (an Oscar-viable Ethan Hawke) on the opening night of the hit Broadway musical “Oklahoma!” penned by Hart’s former collaborators Rodgers and Hammerstein; that film is also in theaters.

‘Hedda’ (2025)

In this randy cinematic adaptation of Henrik Ibsen’s classic, Norway-set play, a man spies his wife rigorously fornicating with a lanky young man in the shadows of a hedgerow, then storms into the fray of a raucous ballroom party – gun drawn – and proclaims, “Whoever’s been fucking my wife, I’m going to shoot you!” To which a wry woman in the crowd responds, “You don’t have enough bullets.” That’s the ribald tenor of this gorgeously shot and immaculately staged period piece directed by Nia DaCosta, who redeems herself nicely after the woefully stilted “The Marvels,” one of the worst films of 2023. Other updates are a setting relo to London in the 1950s, and that our Hedda is a woman of color played with sublime subversive sexuality by Tessa Thompson (“Passing,” “Creed III”). In the mix is Hedda’s former lover, Løvborg (played by Nina Hoss, effective as Cate Blanchett’s wife in “Tár” and a driving force here), whose presence threatens her marriage to George (Tom Bateman), a title-rich yet house-poor aristocrat. The gender flip of Løvborg would’ve made Henry James, chronicler of Boston marriages, proud. Adding fuel to the fire is the fact that George is a struggling academic, whose chief intellectual rival at university is Løvborg. The play/film is essentially a long night of drinking and debauchery at Hedda and George’s grand manse, where past relations, sexual impulses emboldened by alcohol and hidden agendas sit as powder kegs, lit and on the edge of exploding. It’s also about Hedda’s struggles against social norms, and issues of race and womanhood make for subtle daggers. DaCosta’s “Hedda” is a comically dark “Downton Abbey” gone dirty, a rendering that works mostly because of Thompson’s irrepressible performance and the slick, opulent camerawork by Sean Bobbitt (“12 Years a Slave”).

‘Lurker’ (2025)

Alex Russell, a writer on the acclaimed streaming series “The Bear” and “Beef,” keeps his foot on the interpersonal, interracial and social-strata-dividing gas here with this feature debut about a hyperpassive-aggressive interloper who catches the coattails of a rising pop star and becomes an obsessive part of the star’s entourage. The wide-eyed Théodore Pellerin stars as Matthew, a soft-spoken retail worker at a bougie boutique who, through circumstance, drifts into the orbit of a rising pop star known mononymously as Oliver (Archie Madekwe). Matthew goes quickly from wardrobe consultant-gofer to videographer and documentary filmmaker, knocking Oliver’s former go-to from the post “All About Eve”-style. Life is good for a hot moment until Matthew’s retail bestie Jamie (Sunny Suljic, “The Killing of a Sacred Deer”) latches on and threatens to sever Matthew’s status. Pellerin (“Boy Erased,” “Never Rarely Sometimes Always”) does a good job of transitioning from sheepish fanboy to emboldened collaborator and ultimately, egomaniacal manipulator. The slack, amiable personality of Oscar, well done by Madekwe (the baiting bestie in “Saltburn”), is essential to the film, as he welcomes with deep affection only to have who’s in and out shift mercurially. It’s not malice, but a product of his industry and artistry (the soft rap harmonies are one of the weaker sells of the film) and another sharp exploration by Russell, who clearly relishes the small things that bind and divide us, putting another edgy test before us to reflect upon our own sense of moral values.

Leave a comment