Bicyclists ride a Cambridge rotary Friday to honor three victims of fatal crashes.

More than 700 bicyclists came Friday to ride three times around the Cambridge rotary where Memorial Drive intersects with the Boston University Bridge – once for each of the riders who have died on Cambridge Streets over the past four months: Minh-Thi Nguyen and Kim Staley, who were struck and killed in June, and John Corcoran, who was killed Monday on a sidewalk by the nearby DeWolfe Boathouse.

The rush-hour protest was put on by the Boston chapter of Critical Mass, an organization with branches in several hundred cities worldwide that hold group rides to promote street safety and advocate for better cycling infrastructure.

Riders met at the Boston Public Library for a brief rally before heading to the bridge near the boathouse where Corcoran was struck. The ride continued down Memorial Drive before heading back into Boston across the Harvard Bridge, ending at Boston Common. The ride was well organized, with ride marshals giving commands to stop or mass up to obey the rules of the road or to let cars out caught in the throng of riders.

Critical Mass had gone dormant in the area for nearly eight years because many members felt there was a confrontational aspect growing among the ridership. Citywide group rides morphed into the Boston Bike Party, which had a more festive and less activist evening events; Critical Mass rides targeted rush hours on the fourth Friday of every month.

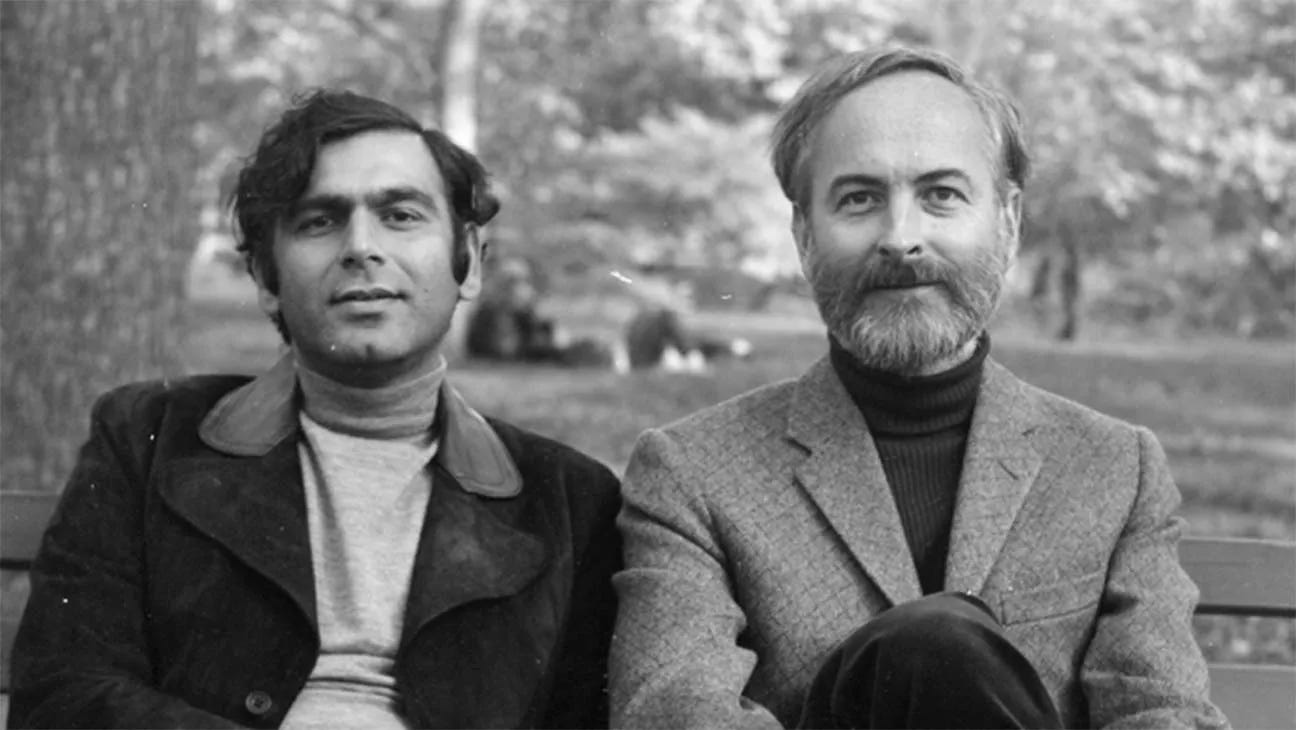

Bicyclists gather in Boston on Friday before riding into Cambridge for a memorial. (Photo: Tom Meek)

The dedication of Corcoran’s ghost bike was held Saturday at the BU boathouse. In attendance were Corcoran’s family and friends and about 100 cyclists and other community members.

Ghost bikes mark where cyclists have died; a bike painted white is chained at the site permanently. “We have placed too many of these,” MassBike director and volunteer ghost bike committee organizer Galen Mook said at the ceremony.

The service was co-led by the Revs. James Weldon, Corcoran’s minister at the Parish of the Good Shepherd in Newton, and Laura Everett, a bike advocate and part of the ghost bike committee. Weldon biked to the ceremony and was clad for it. The bike was donated by Bikes Not Bombs in Boston’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood and painted by committee member Peter Cheung. The ceremony focused on community and grief for Corcoran, an investment manager who was remembered as a kind and giving spirit with strong ties to Harvard University, where his son and daughter – who were in attendance – are a senior and a junior.

The ghost bike placed Saturday in honor of John Corcoran.

There was a time for advocacy and a push for change, but that was not the purpose Saturday, Mook said in remarks to the crowd. They were hard to discern as cars on Memorial Drive zipped by fast enough to make attendees on the sidewalk uncomfortable.

“We’ve been begging the DCR for seven years to make changes to this road, and we’ve been continually ghosted,” said Jamie Katz-Christy, head of the Green Streets Initiative and a member of the Cambridge Bicycle Safety Group and Memorial Drive Alliance. She referred to the state Department of Conservation and Recreation, which oversees the road.

A department spokesperson told The Boston Globe on Wednesday that work was underway “to introduce additional bike lanes to this area of Memorial Drive to improve safety for both cyclists and pedestrians.” (Mook countered that “They’ve known this is a problem” for years.)

The penultimate part of the ceremony was a “litany of grief and gratitude” before the family came forward to dedicate the ghost bike amid a chant of “from a place of death to a place of life.”