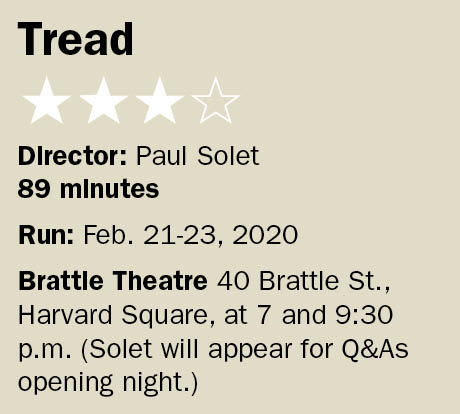

‘Creem: America’s Only Rock ’n’ Roll Magazine’: In on the joke, and at least once on with the band

By Tom Meek

The original title to this nostalgic dial back was “Boy Howdy! The Story of Creem Magazine,” the “Boy Howdy” being the rock magazine’s identifying icon, conjured up by legendary cartoonist Robert Crumb (allegedly in exchange for the mag covering the costs of a medical treatment). The posted title of Scott Crawford’s documentary reflects the storied magazine’s sub-banner, an intentional eff-you to “Rolling Stone,” which launched a few months earlier. As the talking heads in the film have it – including former editors and writers there – “Rolling Stone” was a highbrow culture magazine, while “Creem,” named after the rock group Cream, was just about rock ’n’ roll and adoringly true to its Detroit roots throughout its 20-year existence. It was posture and pose versus edgy, raw ardor.

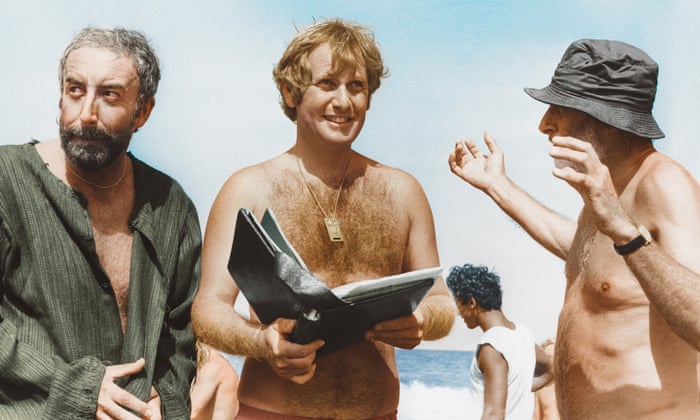

Interestingly, one of those talking heads recalling Creem with such zeal is film director Cameron Crowe (“Singles,” “Jerry McGuire”) whose experience as a Rolling Stone writer gave him the seeds for the bittersweet rock romance “Almost Famous” (2000). Another ardent fan, Chad Smith of the Red Hot Chili Peppers, grew up close enough to bike down to Creem’s offices (described as “aesthetic squalor”) and rues that he never made the pages of the mag. Other rewinds about drop-ins from Detroit rock royalty such as Iggy Pop, Ted Nugent and Alice Cooper dot the film; one time, a Creem journalist embedded with the band Kiss onstage for a show.

The Creem reflected in film feels much like the early days at the Boston Phoenix that I heard about when I joined back in the early 1990s – underground culture, alternative music and cult films, all done for peanuts by hustling journos who’d rather be at a late-night gig and write about it the next day than pull down big dollars as a stolid nine-to-fiver. It was about passion and the vibe, and Crawford gets his finger on that. The film would make a nice double bill with “Other Music,” which also played the Brattle’s Virtual Screening Room this year. The personalities at Creem – including publisher Barry Kramer and critic and editor Lester Bangs, who both died before the magazine flamed out – were clearly a strong and agitated olio. As one surviving commentator said of its legacy and embraced irreverence, “either you’re in on the joke or you were the joke.” Rock on.