‘His Three Daughters’ (2023)

In the latest from Azazel Jacobs (“French Exit”) grief and sisterly differences are wrestled with as familial tensions crest, crash, subside and flow. We open in a small, spare Brooklyn apartment (black pleather couches, an Ikea-esque dining set and no carpeting) as estranged sisters Katie (Carrie Coon), Christina (Elizabeth Olsen) and Rachel (Natasha Lyonne) try to work out the logistics of their terminally ill father’s final hospice cycle. Katie, the oldest, is a bit of a control freak, as evidenced by her telephone disagreements with her husband and teenage daughter back home in California. Christina’s the idealistic free spirit trying to hold the situation together while figuring out the next chapter in her life, and Rachel is the one who’s been living with dad and taking care of him while slacking around the apartment and smoking weed. In short, three very different personalities that, given the heightened emotional state, clash more than not. The three leads deliver genuine, deeply felt performances that ripple with rage, regret and vulnerability. In scope and tenor, “His Three Daughters” is not far off from Florian Zeller’s quietly compelling “The Father” (2020), including a shift in reality that brings home the palpable final punch. The are times the film – which one could imagine as an intimate, in-the-round stage play – gets a bit too cyclical, but usually the dutiful hospice worker named Angel (Rudy Galvan) steps in to update the trio on the changing reality. He’s regarded as both valued family ally and annoying interloper. You never really see or hear the father other than as the sound of a respirator and beeps from a heart monitor reverberating from the back room while the three women in the tiny living room try to make sense of their past, present and future as a family.

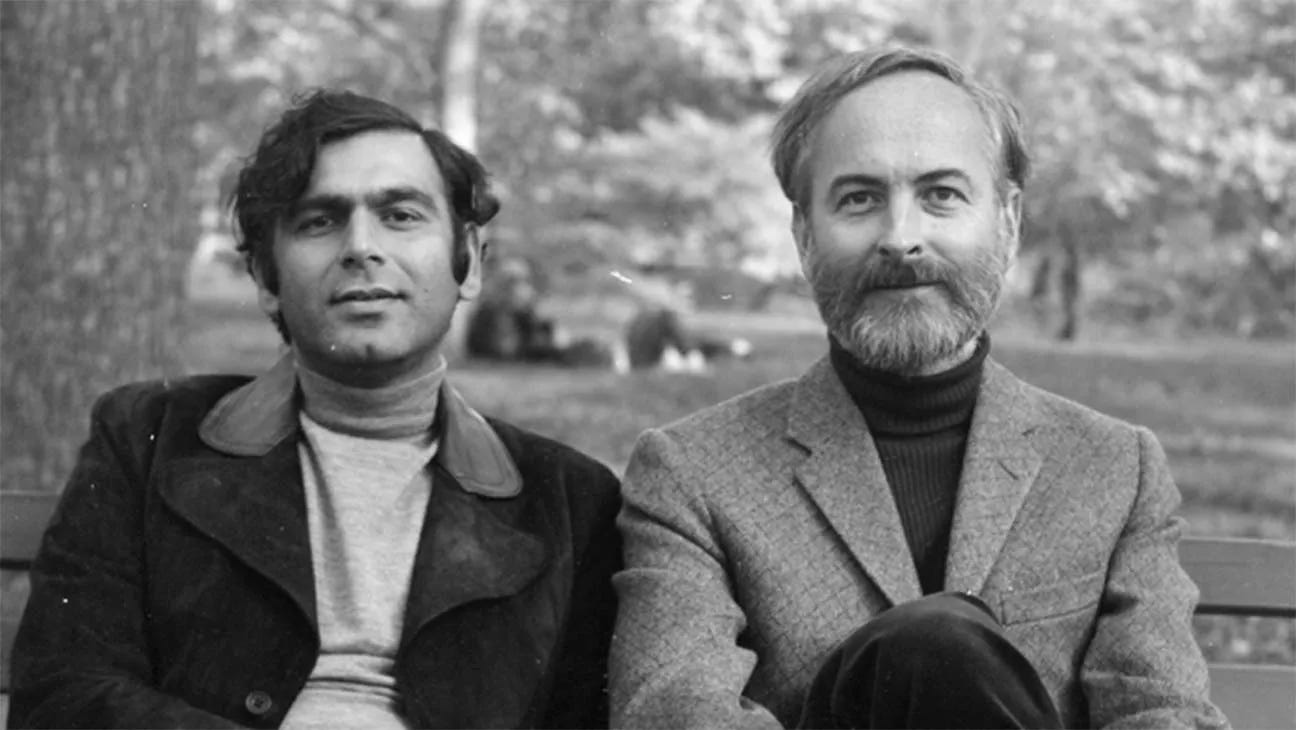

‘Merchant Ivory’ (2024)

Stephen Soucy’s hagiography of the legendary filmmaking tandem that produced such critically acclaimed period dramas as “Howard’s End” (1985), “A Room with a View” (1992) and “Remains of the Day” (1993) puts their output into historical and cultural context and pulls back the veil on the challenges the two faced as a gay couple during less accepting times. Their films were the backbone of art house cinema in the ’80s and ’90s and beyond, until producer Ismail Merchant’s untimely death in 2005. Director James Ivory is still with us and spry in his mid-90s as he offers candid insight into production challenges and his dynamic with Merchant, the high-energy producer always looking to cut costs (you’d be shocked at how little some of these classics were made for) and shill projects to potential investors versus Ivory’s more somber, quiet approach. Soucy gives you the full rewind from Ivory being an adoptee (Ivory notes that the Paul Newman post-Depression, Great War film “Mr. & Mrs. Bridge” felt reflective of his childhood) to Merchant’s upbringing as a Muslim in Northern India, as well as a look into the rest of a production company “family” that included screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, a German-born Jew reared in England (due to a guy named Hitler), and composer Richard Robbins, educated at the New England Conservatory. It was Jhabvala’s prize-winning book “Heat and Dust” that drew interest from Merchant and Ivory; when they chose to adapt, they educed a career shift for Jhabvala, collaborating on 16 films and winning Oscars for “Howard’s End” and “A Room with a View.” Troupe regulars Emma Thompson, Vanessa Redgrave and Helena Bonham Carter are on hand to chime in, as are Hugh Grant, James Wilby and Rupert Graves, who starred together in “Maurice” (1987), a film Soucy and Ivory home in on specifically – not only because of its examination of a closeted gay couple during a time when being gay was a crime in Britain, but because of its powerful context at the time of its release when the AIDs crisis and Act Up were beginning to boil over. The access Soucy earns and Ivory’s frankness create an intimate portrait, including the willingness to concede that some of the team’s later films (“Jefferson in Paris” and “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” among them), while well funded, never registered the kind of critical success as the earlier films. Ivory’s only Oscar came as a writer in 2018 on “Call Me By Your Name.” Breathing in Soucy’s intoxicating love letter, you wish you could go back in time and be part of the Merchant-Ivory “family.” You will also want to go back and rewatch their classics, and perhaps even revisit some of those so-called miscues.

Continue reading