“Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World,” “Small Things Like These” and “The Lost Children”

‘Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World’ (2024)

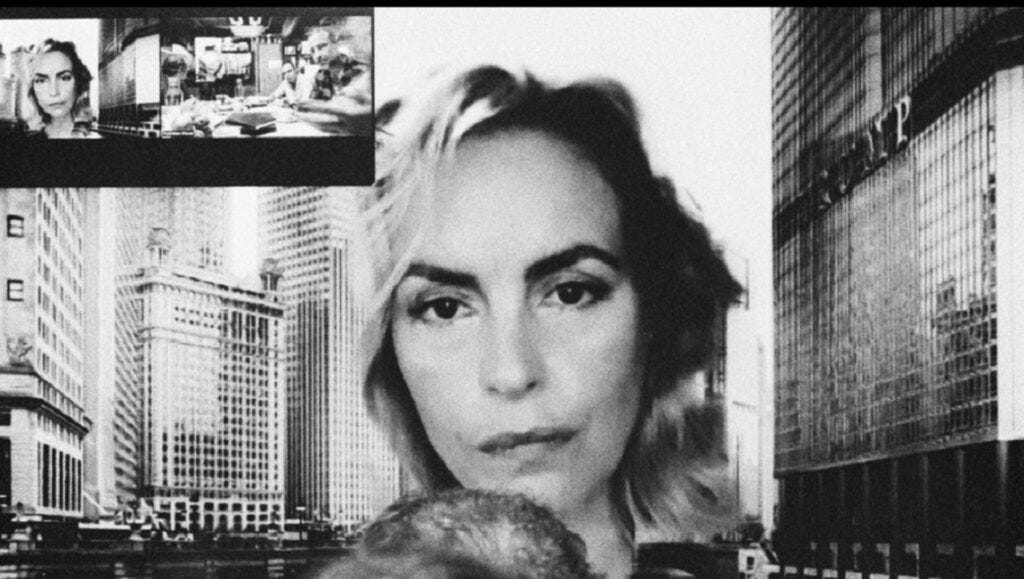

A sardonically black political comedy that’s right out of left field, powered by witty takes on hot topics (Andrew Tate, Putin and Pornhub, to name a few) and a killer performance by Ilinca Manolache, without whom the movie could not be. Manolache plays Angela, a feisty Romanian woman looking to make it in the gig economy as a filmmaker and TikTok sensation. Her main hustle is as a production assistant for a company that makes safety videos, kind of – on many shoots, Angela coaches accident victims, often in wheelchairs, to talk about the safety measures they should have taken to have avoided injury versus the clear negligence of the employer to provide a safe workplace. They’re more CYAs than PSAs, and that’s the degree of biting humor imbued by writer-director Radu Jude (“Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn”).

When we meet Angela, she’s buck naked, on her bedside table is Proust, a half-drunk beer and a glass of wine. From her unapologetic posture as she drags herself out from under the covers at 5 a.m. we know she’s a take-no-shit sort. Donning a sequin dress, Angela wills her way through the day, which includes several safety shoots, chatting with director Uwe Boll about beating the bejesus out of critics who take exception to his lowly regarded films (“BloodRayne,” “Alone in the Dark”), a quickie in her SUV, where nearly half the film takes place, and frequent TikTok dispatches as her evil alter-ego, a bald, bushy-browed incel named Bobiţă who boasts of sexual conquests and hanging out with Tate, the controversial purveyor of all things manly and macho.

Jude employees a unique stylistic palette to frame his modern absurdity; much of Angela in transit is shot in matted black-and-white (reminiscent of Pawel Pawlikowski’s wonderful “Cold War”) while her TikTok and safety videos are shot in color. Jude too infuses footage from the 1981 film “Angela Goes On” about a female cab driver in communist Romania. The thematic juxtaposition (of constantly driving and having a hard time getting from point A to point B) is all about the bureaucratic nonsense that confronts and confounds the two Angelas back during the days of Ceaușescu’s police state and in the capitalist now.

Manolache, who feels like she could slide easily into an early Almodovar or classic Fellini romp, is all-in as the foul-mouthed Angela, full of vim and palpable vigor, and quite muscular and confident in the way she defines her womanhood and place in society. Along with Mickey Madison’s bravura turn in “Anora,” it’s the most pop-off-the-screen performance by an actress this year – Angela and Anora could easily team up and rule the world, and given where we’re heading, that would likely be a good thing.

The ending long take, a filming of a PSA at the site of an accident, is the most somber and dark absurdity in the film, with telling plays on Putin and Ukraine, American TV and the devious use of Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” placards to further victimize and subjugate the maligned.

‘Small Things Like These’ (2024)

Based on Claire Keegan’s novel about the Magdalene Laundries in Ireland, this project directed by Tim Mielants draws emotional depth from an all-in performance by star Cillian Murphy, nearly even more internalized and conflicted here than he was for his Oscar win as Oppenheimer in the Christopher Nolan-helmed biopic last year. The Laundries were a series of so-called asylums for wayward girls, unwed mothers and “fallen women” (former sex workers, recovering addicts, etc.) run by nuns. Keegan’s story targets their sordid history of using women as indentured labor, housing them in prisonlike lockdowns and often taking their babies forcibly from them so the institution could profit from the adoptions. The misdeeds are revealed through the meanderings of Bill Furlong (Murphy), a merchant in 1985 Ireland who provides one such institution with coal. Seeking a signature for an order one day, he witnesses a girl being dragged across the hall screaming. She mouths to him for help. For a frozen second he thinks to act, but the steely eyed sister in charge (Emily Watson) swoops in to explain things away with a cup of tea. Later, Bill discovers a young pregnant girl shackled in the coal shed – yep, it’s that kind of shop of little horrors. Then there’s Bill’s own backstory, his five daughters (his wife is played by Eileen Walsh, who starred in 2002’s “The Magdalene Sisters,” a film that went at the same subject), which serve as a point of reflection and increasing concern, and the boy down the street, often shoeless and starving. Much of what appears quiet, composed and buttoned-down is anything but. The Magdalene Laundries operated from the 1800s to, amazingly, up through the 1990s. In scope, as Mielants and Keegan (“The Quiet Girl”) tell it, “Small Things Like These” feels not too far off from our own Catholic Church abuse scandal (“Spotlight”): cover-ups over decades, victimization of the vulnerable and the leveraging of religious righteousness to make it happen. It’s a somber weaving of disturbing discoveries, but not one without threads of humanity and compassion brought to the screen by Murphy’s deeply emotive performance.

‘The Lost Children’ (2024)

A hackneyed documentary about the incredible true story of survival by four children (ages 11 months to 13 years) in the Colombian rainforest for 40 days after their plane crashed in May of last year. The three adults aboard (including the pilot and the mother of the Indigenous children) perished upon impact. The Colombian military takes up the search and are later joined by a legion of Indigenous volunteers. Directed by Orlando von Einsiedel, Jorge Duran and Lali Houghton, the film focuses hard on this point to showcase the jungle knowledge of the Indigenous searchers and their unease working with the military because, as the film has it, the factions have been at opposite sides of conflicts over decades. Specifics are never really provided, which is one of the film’s major annoyances. The dramatic recreations of the search feel sloppy and staged (often people in arguably real footage have their faces blurred), though the wildlife photography is top shelf. The reason to stay with the film is the chilling footnote that the children’s father and stepfather, Manuel Ranoque, initially at the fore of the search and a seeming heroic figure, is accused (by talking heads, the mother’s aunt and sister) as an abuser, suggesting the children could be evading the search effort to avoid him. The dubbing is mumblecore awful and the staging of Indigenous rituals and ways borders on exploitative arrogance, even though it ostensibly aims to be embracing.