‘His Three Daughters’ (2023)

In the latest from Azazel Jacobs (“French Exit”) grief and sisterly differences are wrestled with as familial tensions crest, crash, subside and flow. We open in a small, spare Brooklyn apartment (black pleather couches, an Ikea-esque dining set and no carpeting) as estranged sisters Katie (Carrie Coon), Christina (Elizabeth Olsen) and Rachel (Natasha Lyonne) try to work out the logistics of their terminally ill father’s final hospice cycle. Katie, the oldest, is a bit of a control freak, as evidenced by her telephone disagreements with her husband and teenage daughter back home in California. Christina’s the idealistic free spirit trying to hold the situation together while figuring out the next chapter in her life, and Rachel is the one who’s been living with dad and taking care of him while slacking around the apartment and smoking weed. In short, three very different personalities that, given the heightened emotional state, clash more than not. The three leads deliver genuine, deeply felt performances that ripple with rage, regret and vulnerability. In scope and tenor, “His Three Daughters” is not far off from Florian Zeller’s quietly compelling “The Father” (2020), including a shift in reality that brings home the palpable final punch. The are times the film – which one could imagine as an intimate, in-the-round stage play – gets a bit too cyclical, but usually the dutiful hospice worker named Angel (Rudy Galvan) steps in to update the trio on the changing reality. He’s regarded as both valued family ally and annoying interloper. You never really see or hear the father other than as the sound of a respirator and beeps from a heart monitor reverberating from the back room while the three women in the tiny living room try to make sense of their past, present and future as a family.

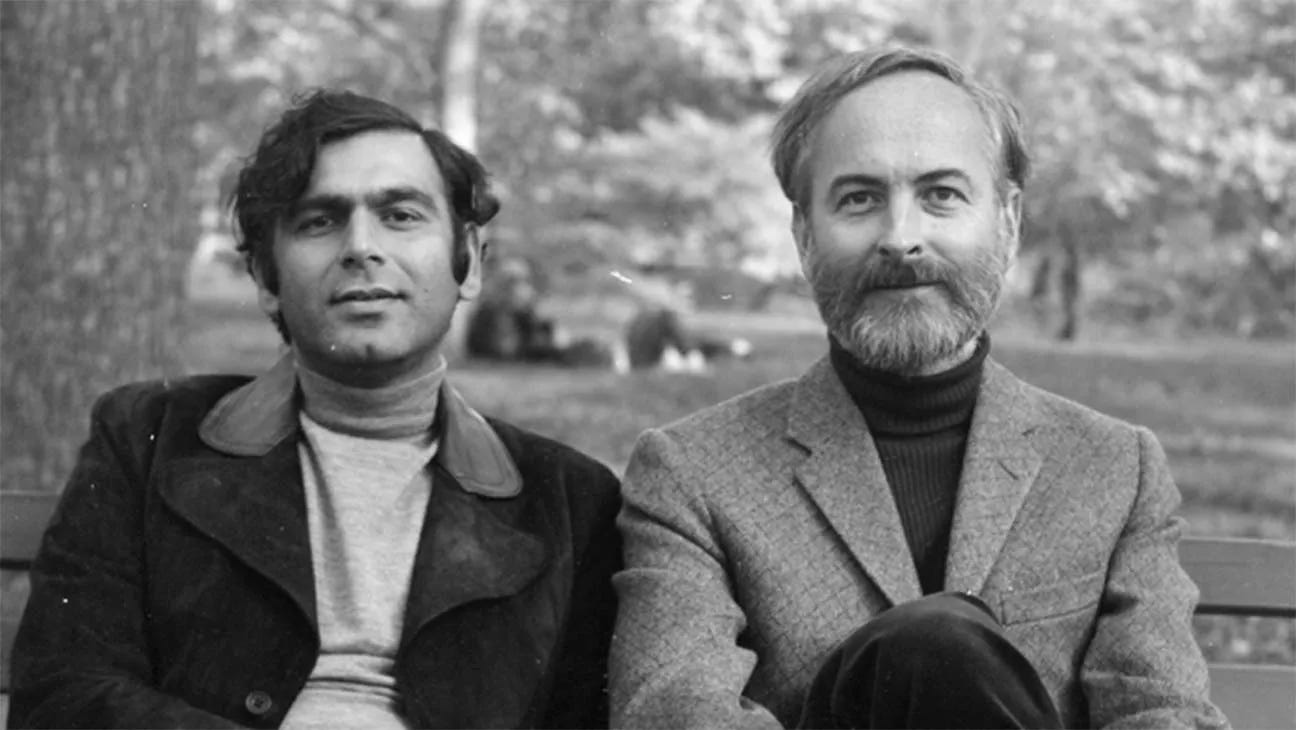

‘Merchant Ivory’ (2024)

Stephen Soucy’s hagiography of the legendary filmmaking tandem that produced such critically acclaimed period dramas as “Howard’s End” (1985), “A Room with a View” (1992) and “Remains of the Day” (1993) puts their output into historical and cultural context and pulls back the veil on the challenges the two faced as a gay couple during less accepting times. Their films were the backbone of art house cinema in the ’80s and ’90s and beyond, until producer Ismail Merchant’s untimely death in 2005. Director James Ivory is still with us and spry in his mid-90s as he offers candid insight into production challenges and his dynamic with Merchant, the high-energy producer always looking to cut costs (you’d be shocked at how little some of these classics were made for) and shill projects to potential investors versus Ivory’s more somber, quiet approach. Soucy gives you the full rewind from Ivory being an adoptee (Ivory notes that the Paul Newman post-Depression, Great War film “Mr. & Mrs. Bridge” felt reflective of his childhood) to Merchant’s upbringing as a Muslim in Northern India, as well as a look into the rest of a production company “family” that included screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, a German-born Jew reared in England (due to a guy named Hitler), and composer Richard Robbins, educated at the New England Conservatory. It was Jhabvala’s prize-winning book “Heat and Dust” that drew interest from Merchant and Ivory; when they chose to adapt, they educed a career shift for Jhabvala, collaborating on 16 films and winning Oscars for “Howard’s End” and “A Room with a View.” Troupe regulars Emma Thompson, Vanessa Redgrave and Helena Bonham Carter are on hand to chime in, as are Hugh Grant, James Wilby and Rupert Graves, who starred together in “Maurice” (1987), a film Soucy and Ivory home in on specifically – not only because of its examination of a closeted gay couple during a time when being gay was a crime in Britain, but because of its powerful context at the time of its release when the AIDs crisis and Act Up were beginning to boil over. The access Soucy earns and Ivory’s frankness create an intimate portrait, including the willingness to concede that some of the team’s later films (“Jefferson in Paris” and “A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries” among them), while well funded, never registered the kind of critical success as the earlier films. Ivory’s only Oscar came as a writer in 2018 on “Call Me By Your Name.” Breathing in Soucy’s intoxicating love letter, you wish you could go back in time and be part of the Merchant-Ivory “family.” You will also want to go back and rewatch their classics, and perhaps even revisit some of those so-called miscues.

‘Speak no Evil’ (2024)

James Watkins’ remake of a 2022 Danish psychological horror flick is a long-simmering burn that compels despite many groan-worthy moments (namely some of the dumbest choices by the knowingly imperiled). The strength of “Speak no Evil” lies in its cast and Watkins’ pacing – something he proved so adept at in his directorial debut, “Eden Lake” (2008), a more riveting chiller similar in tenor and pacing that starred Michael Fassbender. The setup’s fairly simple: Ex-pat Americans Ben and Louise Dalton (Scoot McNairy and Mackenzie Davis, reunited from the show “Halt and Catch Fire”) and their 11-year-old daughter, Agnes (Ali West Leftler), living in London, take a sojourn to a Tuscan resort where they meet Paddy (James McAvoy) and Clara (Aisling Franciosi) and their mute son Ant (Dan Hough). Wine and free-frolicking fun are had as Paddy and Clara’s boundary-pushing antics entice but make the Daltons grinningly uncomfortable. Back in the U.K., the Daltons agree to come for a weekend at Paddy’s farm, so remote that it’s hard get a cellphone signal. There they enjoy a fabulous feast fresh from the farm and sea that would make any foodie envious and some high-octane, homemade hooch to wash it down. But what of the dried bloodstain on the sheets, and Ant trying constantly to communicate with the visitors when out of the gaze of Paddy and Clara? Slow turns start to put the Daltons on edge, though Ben remains numb and plays into Paddy’s games. It’s Louise and Agnes who appreciate the just-fucking-with-you schtick as something that has more profound consequences the longer they stay. How it plays out is “Straw Dogs” (1971) lite. McAvoy, who’s registered feral and mercurial onscreen before (“Atomic Blonde” and “Split”), carries the film with a bravura performance that adeptly avoids going over the edge or into camp; Franciosi, who played the opposite side of the coin in Jennifer Kent’s harrowing “The Nightingale” (2019), is up to the task as his partner in crime, while Davis (“Blade Runner 2049”) and McNairy are nuanced as a couple fraying at the edges, and Leftler (“The Good Nurse”) and Hough register turns beyond their years at critical junctures. It’s not great home-invasion horror, but it does pin you to your seat.

‘Slingshot’ (2024)

In space, no one can hear you scream, or snore, as is the case with this deep space psychological thriller from Mikael Håfström that should have had the retro rockets fired before it launched. The near-future sci-fi premise has something to do with critical human resources to be harvested from Titan – the largest of Saturn’s moons – so we on Earth can keep breathing air. To do so, a crew of three in a hibernation state are launched into space. The plan calls for them to wake up mid-flight to execute the title maneuver around Saturn, snatch the goods, go back into a bear state and head home. As we know from our astronauts stranded on the I.S.S., nothing goes as planned, and such is true in the flat-iron fiction here. One of the astronauts, John (Casey Affleck) has terrible hallucinations from the stasis; the captain is chipper, robust and on course (Laurence Fishburne); Nash (Tomer Capone, Frenchie in “The Boys”), the guy who holds the keys to the console, is concerned, skeptical and paranoid. What ensues is a battle of wills and wits divided over the matter of the ship’s structural integrity. John keeps trying to find solace in the memory of his girlfriend Zoe (Emily Beecham) back home as things look to turn murderous on the ship. The shuffle of realities and timelines as handled by Håfström, who did much better with the futuristic war thriller “Outside the Wire” (2021), is JV mishmash. Affleck, normally reliable (“Good Will Hunting” and “Manchester by the Sea”) feels anemic and miscast here. I’m not sure who would have been a better choice, and it doesn’t much matter, because as twist after twist begins to pile up at the end – there’s a near infinity of ’em – it’s unclear as to where we came from and where we’re going. The golden-baritone Fishburne is commanding in most all his scenes and Beecham (“Little Joe”) shines in her brief few flashbacks, but other than that, “Slingshot” is a hot, messy miasma that, like the vessel at its center, sails slackly forth on AI autopilot.

‘Close Your Eyes’ (2023)

Hard to believe that Spanish director Victor Erice hasn’t made a movie in nearly 30 years. Most renowned for his critically acclaimed “The Spirit of the Beehive” (1973), a village drama built around the screening of the movie “Frankenstein,” Erice’s last feature was the documentary “Dream of Light” (1992) about sunlight-inspired artist Antonio Lopez. To be fair, Erice has kept busy with shorts and anthology collaborations. At a spry 84, his latest, like “Beehive,” centers on a film, in this case an unfinished film. “Close Your Eyes” opens in Spain after its civil war and World War II as an elderly, well-off patriarch implores a younger man to go to Shanghai to search for his now teenage daughter. The how, what and why, are important, but not central to the film, as we jump into the near-now and learn that the scene we just drank in was from that unfinished film, “The Farewell Gaze,” directed by Miguel Solo (Manolo Solo), a weary-eyed lion who hasn’t made a movie in decades and now ekes out a living as a translator. “The Farewell Gaze” was never completed because the the actor who plays the envoy, Julio (José Coronado), disappeared mysteriously. A Spanish television series called “Unresolved Cases” gets on the case and ferrets out Miguel for a fee. There are multiple theories as to what befell Julio. Possibilities range from a cliff fall – suicidal or not – to an illicit affair with a strongman’s wife that was discovered. The true fate, or as close to the truth as can be, comes late in the film, but just as “Close Your Eyes” is not about the making of “Farewell,” it’s not about the fate of Julio: It’s about the journey of a filmmaker late in winter. To say that “Close Your Eyes” is reflective of Erice’s own cinematic arc would be both true and false, but it is an oblique, hypnotic sojourn into the emotional darkness of a filmmaker’s heart.

Leave a comment